急がないと非公開にします急がないと非公開にします急がないと非公開にします急がないと非公開にしますOSの4.xの課題

OSの講義の4.xの問題を解く

これが正解だぜ(どや)みたいなノリでは書いてないです、ただの平均的な技術力を持っているB2が解いているだけ

課題の取り組みをブログで書いてもいいという許可をもらった上で記事を書いてます

最新の課題内容であることや、答えが正しいかどうかは保証しません

このブログの情報で読者に何らかの不都合が生じても著者は責任は取らないです

4.xについて

4.2から4.5はkono先生からメールで各自ランダムな数字を与えられるので、その数字に該当する教科書の問題(Exercisesにある)を解くといったもの

こんな風にメールで問題が与えられる、一人一人が違う問題を与えられる

該当する番号の問題がなかったら好きなの解いていい(って質問チャンネルで書いてた)、ただ簡単すぎるのを選ぶのは...ね?

Your OS assignments for Paperback are Chapter 11 ex 11.15 Chapter 6 ex 6.17 Chapter 12 ex 12.5 Chapter 21 ex 21.15

で、この講義ページの通りに、4.2から4.5までの課題としてこれらの問題を解く

4.1 シミュレータ

このページの問題を解く

level 1 task list を作る

コード

use std::collections::VecDeque;

// Define the `Task` struct, representing a task with a name and the number of clock cycles it consumes.

struct Task {

name: String,

clock_cycles: u32,

}

fn main() {

// Create a queue for tasks. VecDeque allows efficient popping and pushing operations.

let mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task> = VecDeque::new();

}

level 2 task list をファイルから読み込む、あるいは乱数で生成する

コード

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::VecDeque; // Add this to use the random number generator

// Define the `Task` struct, representing a task with a name and the number of clock cycles it consumes.

struct Task {

name: String,

clock_cycles: u32,

}

fn main() {

// Create a queue for tasks. VecDeque allows efficient popping and pushing operations.

let mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task> = VecDeque::new();

// Generate tasks with random clock cycles and add them to the queue

for i in 0..10 {

let task = Task {

name: format!("Task_{}", i),

clock_cycles: rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..101), // Random number between 1 and 100

};

task_queue.push_back(task);

}

// Print each task in the queue

for task in task_queue {

println!("{}: {} clock cycles", task.name, task.clock_cycles);

}

}

実行結果

$ cargo run .

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.04s

Running `target/debug/rust-scheduling-simulator .`

Task_0: 46 clock cycles

Task_1: 45 clock cycles

Task_2: 12 clock cycles

Task_3: 61 clock cycles

Task_4: 18 clock cycles

Task_5: 42 clock cycles

Task_6: 54 clock cycles

Task_7: 42 clock cycles

Task_8: 81 clock cycles

Task_9: 51 clock cycles

level 3 FIFO スケジューラシミュレータを書く

コード

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

// Define the `Task` struct, representing a task with a name and the number of clock cycles it consumes.

struct Task {

name: String,

clock_cycles: u32,

}

// Define the `task_exec` function, which processes tasks in FIFO order

fn task_exec(mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task>) {

while let Some(task) = task_queue.pop_front() {

// Simulate clock cycle consumption with sleep

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(task.clock_cycles.into()));

}

}

fn main() {

// Create a queue for tasks. VecDeque allows efficient popping and pushing operations.

let mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task> = VecDeque::new();

// Generate tasks with random clock cycles and add them to the queue

for i in 0..10 {

let task = Task {

name: format!("Task_{}", i),

clock_cycles: rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..101), // Random number between 1 and 100

};

task_queue.push_back(task);

}

task_exec(task_queue);

}

level 4 結果を表示する

コード

use rand::Rng;

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

// Define the `Task` struct, representing a task with a name and the number of clock cycles it consumes.

struct Task {

name: String,

clock_cycles: u32,

}

// Define the `task_exec` function, which processes tasks in FIFO order

fn task_exec(mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task>) {

while let Some(task) = task_queue.pop_front() {

println!(

"Executing {}: {} clock cycles",

task.name, task.clock_cycles

);

// Simulate clock cycle consumption with sleep

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(task.clock_cycles.into()));

}

}

fn main() {

// Create a queue for tasks. VecDeque allows efficient popping and pushing operations.

let mut task_queue: VecDeque<Task> = VecDeque::new();

// Generate tasks with random clock cycles and add them to the queue

for i in 0..10 {

let task = Task {

name: format!("Task_{}", i),

clock_cycles: rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..101), // Random number between 1 and 100

};

task_queue.push_back(task);

}

task_exec(task_queue);

}

実行結果

$ cargo run .

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.04s

Running `target/debug/rust-scheduling-simulator .`

Executing Task_0: 9 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 37 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 67 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 47 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 32 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 89 clock cycles

Executing Task_6: 73 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 74 clock cycles

Executing Task_8: 77 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 83 clock cycles

level 5 sfj / round robin などを書く

「Abstract factory pattern を使って、scheduling algorithm を切り替える」という指示もある

コード

use rand::Rng;

use std::cmp::Reverse;

use std::collections::BinaryHeap;

use std::collections::VecDeque;

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

// Define the `Task` struct, representing a task with a name and the number of clock cycles it consumes.

#[derive(Eq, PartialEq, Clone)]

struct Task {

name: String,

clock_cycles: u32,

}

// Implement Ord and PartialOrd to use Task in a BinaryHeap (for SJF scheduling).

impl Ord for Task {

fn cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> std::cmp::Ordering {

self.clock_cycles.cmp(&other.clock_cycles)

}

}

impl PartialOrd for Task {

fn partial_cmp(&self, other: &Self) -> Option<std::cmp::Ordering> {

Some(self.cmp(other))

}

}

// Define a trait for scheduling algorithms

trait Scheduler {

fn push(&mut self, task: Task);

fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<Task>;

}

// FIFO Scheduler

struct FIFOScheduler(VecDeque<Task>);

impl Scheduler for FIFOScheduler {

fn push(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.0.push_back(task);

}

fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<Task> {

self.0.pop_front()

}

}

// SJF Scheduler

struct SJFScheduler(BinaryHeap<Reverse<Task>>);

impl Scheduler for SJFScheduler {

fn push(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.0.push(Reverse(task));

}

fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<Task> {

self.0.pop().map(|reverse| reverse.0)

}

}

// Round Robin Scheduler

struct RRScheduler {

queue: VecDeque<Task>,

quantum: u32,

}

impl Scheduler for RRScheduler {

fn push(&mut self, task: Task) {

self.queue.push_back(task);

}

fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<Task> {

if let Some(mut task) = self.queue.pop_front() {

if task.clock_cycles > self.quantum {

task.clock_cycles -= self.quantum;

self.queue.push_back(task.clone());

Some(Task {

name: task.name,

clock_cycles: self.quantum,

})

} else {

Some(task)

}

} else {

None

}

}

}

fn task_exec<S: Scheduler>(mut scheduler: S) {

while let Some(task) = scheduler.pop() {

println!(

"Executing {}: {} clock cycles",

task.name, task.clock_cycles

);

// Simulate clock cycle consumption with sleep

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(task.clock_cycles.into()));

}

}

fn main() {

// Create tasks. VecDeque allows efficient popping and pushing operations.

let tasks: Vec<Task> = (0..10)

.map(|i| {

Task {

name: format!("Task_{}", i),

clock_cycles: rand::thread_rng().gen_range(1..101), // Random number between 1 and 100

}

})

.collect();

println!("FIFO Scheduler:");

let fifo_scheduler = FIFOScheduler(VecDeque::from(tasks.clone()));

task_exec(fifo_scheduler);

println!("\nSJF Scheduler:");

let sjf_scheduler = SJFScheduler(tasks.iter().cloned().map(Reverse).collect());

task_exec(sjf_scheduler);

println!("\nRound Robin Scheduler:");

let rr_scheduler = RRScheduler {

queue: VecDeque::from(tasks),

quantum: 20,

};

task_exec(rr_scheduler);

}

実行結果

$ cargo run .

Compiling rust-scheduling-simulator v0.1.0 (/Users/yoshisaur/workspace/lectures/operating-system/uryukyu-lecture-OS/4.x/4.1/rust-scheduling-simulator)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.46s

Running `target/debug/rust-scheduling-simulator .`

FIFO Scheduler:

Executing Task_0: 44 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 36 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 38 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 84 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 7 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 40 clock cycles

Executing Task_6: 1 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 73 clock cycles

Executing Task_8: 21 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 61 clock cycles

SJF Scheduler:

Executing Task_6: 1 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 7 clock cycles

Executing Task_8: 21 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 36 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 38 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 40 clock cycles

Executing Task_0: 44 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 61 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 73 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 84 clock cycles

Round Robin Scheduler:

Executing Task_0: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 7 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_6: 1 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_8: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_0: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 16 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 18 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_8: 1 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_0: 4 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_7: 13 clock cycles

Executing Task_9: 1 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 4 clock cycles

level 7 Gannt Chart を書く、複数のタスクのスケジューリングを表す時間を横軸としたグラフを描く

実行結果

出力したグラフはここにある。

level 8 Periodical task

Ratemonotonic なスケジューラを書く

実行結果

RMS Scheduler: Executing Task_2: 49 clock cycles, period: 113 Executing Task_0: 53 clock cycles, period: 131 Executing Task_7: 2 clock cycles, period: 144 Executing Task_4: 65 clock cycles, period: 145 Executing Task_8: 65 clock cycles, period: 149 Executing Task_5: 41 clock cycles, period: 167 Executing Task_3: 47 clock cycles, period: 177 Executing Task_9: 83 clock cycles, period: 178 Executing Task_6: 57 clock cycles, period: 190 Executing Task_1: 84 clock cycles, period: 200

level 9 scheduling rust thread、thread 自体を schedule する方法を考案し、rust に実装せよ

前提として、スレッドのスケジューリングはOSの役割でRustの標準APIではそのスケジューリングを操作することはできない。Mutex, Condvarを用いてスレッドを間接的にスケジュールすることはできる。

実行結果

$ cargo run .

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.02s

Running `target/debug/rust-scheduling-simulator-level9 .`

FIFO Scheduler:

Executing Task_1: 71 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 70 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 34 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 58 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 67 clock cycles

SJF Scheduler:

Executing Task_3: 34 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 58 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 67 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 70 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 71 clock cycles

Round Robin Scheduler:

Executing Task_1: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_3: 14 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_4: 18 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 20 clock cycles

Executing Task_1: 11 clock cycles

Executing Task_2: 10 clock cycles

Executing Task_5: 7 clock cycles

4.2 教科書の問題 Chapter 7 ex 7.7

メールでは11.15と書かれていたがChapter 11に問題がなかった

7章(Interprocess Communication)から問題を選ぶ

7.7が面白そう

教科書の7.7の問題を解く、問題文は以下の通り、

In this example the character names bear similarity with the Gauls. Gauls have a chief evaluator of art. His name is Evalutrix and his job is to evaluate every piece of art which is brought in the Gaul land. He has advisors whose names are Moodix, Chancix, and Gamblix. When a piece of art is brought up to Evalutrix he contacts his advisors indicating the likely base price. The three advisors use the following systems to indicate their evaluations.

a. Chancix always tosses a coin. If it is heads he increases the evaluation by 5 per cent. If it is tails, he reduces the evaluation by 5 per cent.

b. Gamblix shuffles a pack of cards and draws a card from it. The face value of the card determines the percentage change he would suggest. If the card is a one from the black suit, he increases the evaluation. If it is from the red suit, then he decreases the evaluation.

c. Moodix always takes a look at the real-time clock on his system. He adds up the digits in hours, and minutes and subtracts 15 from it. Whatever the result is, that percentage change in value he communicates to Evalutrix.

Evalutrix averages all the values including his own base price and declares the result as the value of the art. Simulate Evalutrix as the parent process, and his advisors as child processes with the base price being given as the inline argument.

和訳

この例では、登場人物名がガリア人のと似ている。ガリア人には芸術品の最高評価者が存在し、その名をEvalutrixという。彼には、Moodix、Chancix、Gamblixという名のアドバイサーがいる。美術品がEvalutrixに持ち込まれると、彼はアドバイサー3人に連絡して、その芸術品の基本価格を提示する。3人のアドバイサーは、以下のような方法で評価をする。 a. Chancixはコインを投げて、表が出れば5%上げる、裏が出れば5%下げる。 b. Gamblixはカードのパックをシャッフルして、そこからカードを1枚引き黒のスートならば評価を上げて、赤のスートならば評価を下げる。カードの番号が提示する変化の割合(%)を決定する。 c. Moodixは、時計を見る。時計の「時」と「分」の数字を足し合わせて、15を引く。その値の変化の割合(%)をEvalutrixに伝える。 Evalutrixは、自分の基本価格とa, b, cの提示した値の平均をとって、その結果を芸術品の価値として、宣言する。 Evalutrixを親プロセスと、アドバイサー達を基本価格をインライン引数とする子プロセスとしてシミュレートしなさい。

解く

システムコール(fork)を使いプロセスを生成して、パイプ(pipe)によるプロセス間通信をする

上記の操作をC言語で実装してEvalutrixを親プロセス、アドバイサー達を子プロセスとして扱い、芸術品の価値を決定するスクリプトを作成する

この問題では「単一の親プロセス」と「複数の子プロセス」とのプロセス間通信をするC言語スクリプトを書くことが求められている

答え(日本語)

Cのコードを書いた

#include <unistd.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <time.h>

#define READ (0)

#define WRITE (1)

#define CHANCIX (0)

#define GAMBLIX (1)

#define MOODIX (2)

#define HEADS (1)

#define TAILS (0)

#define BLACK_SUIT (1)

#define RED_SUIT (0)

int calculate_chancix_value(int basic_price) {

srand((unsigned int)time(NULL));

int flipped_coin = rand() % 2;

int chancix_value = basic_price;

if (flipped_coin == HEADS) {

chancix_value += basic_price * 0.05;

} else if (flipped_coin == TAILS) {

chancix_value -= basic_price * 0.05;

}

printf("The price Chancix evaluates: %d\n", chancix_value);

return chancix_value;

}

int calculate_gamblix_value(int basic_price) {

srand((unsigned int)time(NULL));

int card_suit = rand() % 2;

int card_num = rand() % 13 + 1;

int gamblix_value = basic_price;

if (card_suit == BLACK_SUIT) {

gamblix_value += basic_price * card_num / 100.0;

} else if (card_suit == RED_SUIT) {

gamblix_value -= basic_price * card_num / 100.0;

}

printf("The price Gamblix evaluates: %d\n", gamblix_value);

return gamblix_value;

}

int calculate_moodix_value(int basic_price) {

time_t seconds;

struct tm *timeStruct;

seconds = time(NULL);

timeStruct = localtime(&seconds);

int hours = timeStruct->tm_hour;

int minutes = timeStruct->tm_min;

int moodix_value = basic_price;

// add the hours and minutes in Japan time, subtract by 15, and devide by 100

moodix_value += basic_price * ((hours + 9) % 24 + minutes - 15) / 100.0;

printf("The price Moodix evaluates: %d\n", moodix_value);

return moodix_value;

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

const int CHILD_PROCESS_NUM = 3;

pid_t process_ids[CHILD_PROCESS_NUM];

char pipe_input[256], pipe_output[256];

int parent2child_pipes[CHILD_PROCESS_NUM][2];

int child2parent_pipes[CHILD_PROCESS_NUM][2];

int p_i, close_i;

int parent2child_pipe_status, child2parent_pipe_status;

int basic_price, evaluated_price, price_sum, price_average;

// prompt user input to set the base price

printf("The basic price is ");

fgets(pipe_input, 256, stdin);

printf("The price Evalutrix indicates: %s", pipe_input);

price_sum = atoi(pipe_input);

for (p_i = 0; p_i < CHILD_PROCESS_NUM; ++p_i) {

parent2child_pipe_status = pipe(parent2child_pipes[p_i]);

child2parent_pipe_status = pipe(child2parent_pipes[p_i]);

// if either a parent2child pipe or a child2parent pipe fails to open

if (parent2child_pipe_status < 0 || child2parent_pipe_status < 0) {

// close all proccesses' exisiting pipes

for (close_i = 0; close_i < p_i; ++close_i) {

close(parent2child_pipes[close_i][READ]);

close(parent2child_pipes[close_i][WRITE]);

close(child2parent_pipes[close_i][READ]);

close(child2parent_pipes[close_i][WRITE]);

}

// if a child2parent pipe fails to open

if (child2parent_pipe_status < 0) {

// close the most recently opened parent2child_pipe

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][READ]);

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][WRITE]);

}

return 1;

}

}

for (p_i = 0; p_i < CHILD_PROCESS_NUM; ++p_i) {

process_ids[p_i] = fork();

// if a child process fails to be generated

if (process_ids[p_i] < 0) {

// close all processes' pipes

for (close_i = 0; close_i < CHILD_PROCESS_NUM; ++close_i) {

close(parent2child_pipes[close_i][READ]);

close(parent2child_pipes[close_i][WRITE]);

close(child2parent_pipes[close_i][READ]);

close(child2parent_pipes[close_i][WRITE]);

}

return 1;

// if the current process is a child process

} else if (process_ids[p_i] == 0) {

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][WRITE]);

close(child2parent_pipes[p_i][READ]);

read(parent2child_pipes[p_i][READ], pipe_input, 256);

basic_price = atoi(pipe_input);

evaluated_price = basic_price;

if (p_i == CHANCIX) {

// do what Chancix does

evaluated_price = calculate_chancix_value(basic_price);

} else if (p_i == GAMBLIX) {

// do what Gamlix does

evaluated_price = calculate_gamblix_value(basic_price);

} else if (p_i == MOODIX) {

// do what Moodix does

evaluated_price = calculate_moodix_value(basic_price);

}

sprintf(pipe_input, "%d", evaluated_price);

write(child2parent_pipes[p_i][WRITE], pipe_input, strlen(pipe_input) + 1);

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][READ]);

close(child2parent_pipes[p_i][WRITE]);

exit(0);

// if the current process is the parent process

} else if (process_ids[p_i] > 0) {

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][READ]);

close(child2parent_pipes[p_i][WRITE]);

write(parent2child_pipes[p_i][WRITE], pipe_input, strlen(pipe_input) + 1);

read(child2parent_pipes[p_i][READ], pipe_output, 256);

price_sum += atoi(pipe_output);

close(parent2child_pipes[p_i][WRITE]);

close(child2parent_pipes[p_i][READ]);

}

}

price_average = price_sum / (CHILD_PROCESS_NUM + 1);

printf("The price to declare is %d\n", price_average);

}

パイプについて

- プロセス同士でデータをやり取りするためにはパイプを作成する必要がある

- 1本のパイプで一方向(親->子、子->親のいずれか)のデータの送信が可能になる

- つまり、今回の問題のように双方向でデータのやりとりを行うためにはプロセス間で2本のパイプ(親->子、子->親の両方)が必要になる

- コードの104行目から135行目までがパイプを作成する部分である

- 途中でパイプの作成に失敗したら、今まで作成したパイプを閉じる必要がある

- 親->子のパイプを作成したときに、パイプの読み出し用と書き込み用の2つのディスクリプタが作られる

- 子->親のパイプを作成したときに、パイプの読み出し用と書き込み用の2つのディスクリプタが作られる

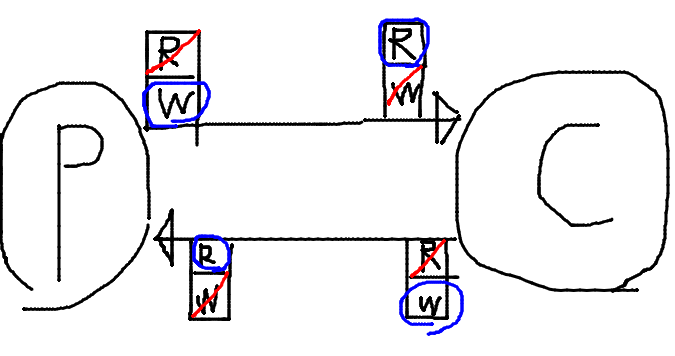

- 以下が説明したプロセス間通信の図である

フォークについて

- パイプを作成したあとはプロセスをフォークして親プロセスと子プロセスに分ける

- プロセスのidを使ってif文の分岐で親プロセスと子プロセスの処理を記述する

- 子プロセスの処理の最後に186行目のように

exit(0)を加えて子プロセスを正常に終了させる必要がある

- 子プロセスの処理の最後に186行目のように

シュミレートする

実行結果(4:01a.m.に実行)

The basic price is 10000 The price Evalutrix indicates: 10000 The price Chancix evaluates: 9500 The price Gamblix evaluates: 9700 The price Moodix evaluates: 9000 The price to declare is 9550

実行結果(4:02a.m.に実行)

The basic price is 10000 The price Evalutrix indicates: 10000 The price Chancix evaluates: 10500 The price Gamblix evaluates: 11000 The price Moodix evaluates: 9100 The price to declare is 10150

実行結果(4:03a.m.に実行)

The basic price is 10000 The price Evalutrix indicates: 10000 The price Chancix evaluates: 10500 The price Gamblix evaluates: 10500 The price Moodix evaluates: 9200 The price to declare is 10050

すべての値が想定する範囲内で値が変動していることを確認した

4.2の感想

- めっちゃ面白い

- C言語楽しい

- プロセス間通信って面白い!

4.3 教科書の問題 Chapter 6 ex 6.8

メールでは6.17と書いてたが問題が存在しなかったので、6章の中の面白そうな問題を選んだ

教科書の6.8の問題を解く、問題文は以下の通り、

Dining philosophers problem:

This is a very famous and often quoted problem in OS research. It reflects considerable degree of concurrency in operation. It also requires synchronisation of actions. We will assume that the philosophers are all Japanese and love eating the Japanese rice (Gohan in Japanese). Five philosophers sit around a circular table. Each philosopher spends his life alternatively thinking and eating. In the centre of the table is a bowl of rice and there is a plate in front of each philosopher. Clearly, philosophers would need two chopsticks to have a helping of rice. The philosophers have five chopsticks which are placed between their plates. So each plate has a chopstick to its right and to its left. The philosophers only use the chopsticks to their immediate right and left.

How would the philosophers need to schedule their thinking and eating?

(Hint: Think of each chopstick as a semaphore.)

和訳

dining philosophers問題:

OSの研究において非常に有名でよく引用される問題である。哲学者はみんな日本のご飯を食べるのが大好きな日本人で、全員で5人が円卓を囲んでいると想定する。哲学者はそれぞれ全員、考えることと食べることを交互に繰り返して暮らしている。テーブルの中心にはご飯が盛られたボウルがあり、哲学者一人一人の前に皿が置かれている。ご飯を食べるには箸が2本(1膳)必要である。哲学者達は合わせて5本の箸を持ち、それぞれの皿の間に置いている。つまり、皿の右側と左側に1本の箸があるということを意味する。哲学者はすぐ右と左の箸しか使えない。

哲学者たちは、どのように思考と食事のスケジュールを立てるべきか?

答え(日本語)

ナイーブな実装のデッドロック

- まずはDining Philosophers 問題を愚直に実装しデッドロックさせる

- 全員、左の箸を取ってから右の箸を取って思考と食事をする

- 全員が左の箸を持ったまま右の箸を待ち続ける状態になればデッドロック

use rand::Rng;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

const PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT: usize = 5;

fn philosopher(

id: usize,

left_chopstick: Arc<Mutex<()>>,

right_chopstick: Arc<Mutex<()>>,

right_chopstick_counter: Arc<Mutex<usize>>,

) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

loop {

println!("Philosopher {} is thinking", id);

{

let _left_guard = left_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the left chopstick.", id);

{

let mut counter = right_chopstick_counter.lock().unwrap();

*counter += 1;

}

println!(

"Philosopher {} is trying to pick up the right chopstick.",

id

);

let _right_guard = right_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the right chopstick.", id);

{

let mut counter = right_chopstick_counter.lock().unwrap();

*counter -= 1;

}

let eat_duration = rng.gen_range(0..10000);

println!("Philosopher {} is eating.", id);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(eat_duration));

println!("Philosopher {} dropped the right chopstick.", id);

println!("Philosopher {} dropped the left chopstick.", id);

}

}

}

fn deadlock_detector(counter: Arc<Mutex<usize>>) {

loop {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(10));

let c = {

let count = counter.lock().unwrap();

*count

};

if c == PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT {

println!("DEADLOCK DETECTED!");

break;

}

}

}

fn main() {

let chopsticks: Vec<_> = (0..PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT)

.map(|_| Arc::new(Mutex::new(())))

.collect();

let right_chopstick_counter = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

let mut handles = vec![];

for i in 0..PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT {

let left_chopstick = chopsticks[i].clone();

let right_chopstick = chopsticks[(i + 1) % PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT].clone();

let counter_clone = right_chopstick_counter.clone();

handles.push(thread::spawn(move || {

philosopher(i, left_chopstick, right_chopstick, counter_clone)

}));

}

let detector_handle = thread::spawn({

let counter_clone = right_chopstick_counter.clone();

move || deadlock_detector(counter_clone)

});

for handle in handles {

handle.join().unwrap();

}

detector_handle.join().unwrap();

}

実行時のログ

$ cargo run

Compiling dining-philosophers-fail v0.1.0 (/Users/yoshisaur/workspace/lectures/operating-system/uryukyu-lecture-OS/4.x/4.3/dining-philo

sophers-fail)

Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.42s

Running `target/debug/dining-philosophers-fail`

Philosopher 4 is thinking

Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 picked up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is thinking

Philosopher 2 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 3 is thinking

Philosopher 1 is thinking

Philosopher 2 picked up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 1 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 1 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 0 is thinking

Philosopher 2 is eating.

Philosopher 4 is eating.

Philosopher 2 dropped the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 dropped the left chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is thinking

Philosopher 2 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 picked up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is eating.

Philosopher 4 dropped the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 dropped the left chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is thinking

Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 picked up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is eating.

Philosopher 2 dropped the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 dropped the left chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is thinking

Philosopher 2 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 3 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 3 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 2 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 dropped the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 dropped the left chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is thinking

Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 0 picked up the left chopstick.

Philosopher 0 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

Philosopher 4 is trying to pick up the right chopstick.

DEADLOCK DETECTED!

最後の哲学者だけ箸を取る順番を変える実装

- デッドロックにならないためには、すべての哲学者が同時に右の箸を取り上げようとしないようにすることが重要

- 最後の哲学者だけが逆の順序(左の箸を先に取り上げる)で箸を取り上げるようにすれば、すべての哲学者が同時に右の箸を取り上げようとしなくなるので、デッドロックにならない

use rand::Rng;

use std::sync::{Arc, Mutex};

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

const PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT: usize = 5;

fn philosopher(id: usize, left_chopstick: Arc<Mutex<()>>, right_chopstick: Arc<Mutex<()>>) {

let mut rng = rand::thread_rng();

loop {

println!("Philosopher {} is thinking", id);

if id == PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT - 1 {

let _left_guard = left_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the left chopstick.", id);

let _right_guard = right_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the right chopstick.", id);

} else {

let _right_guard = right_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the right chopstick.", id);

let _left_guard = left_chopstick.lock().unwrap();

println!("Philosopher {} picked up the left chopstick.", id);

}

let eat_duration = rng.gen_range(0..10000);

println!("Philosopher {} is eating.", id);

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(eat_duration));

println!("Philosopher {} dropped the right chopstick.", id);

println!("Philosopher {} dropped the left chopstick.", id);

}

}

fn main() {

let chopsticks: Vec<_> = (0..PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT)

.map(|_| Arc::new(Mutex::new(())))

.collect();

let mut handles = vec![];

for i in 0..PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT {

let left_chopstick = chopsticks[i].clone();

let right_chopstick = chopsticks[(i + 1) % PHILOSOPHERS_COUNT].clone();

handles.push(thread::spawn(move || {

philosopher(i, left_chopstick, right_chopstick)

}));

}

for handle in handles {

handle.join().unwrap();

}

}

実行時ログ

Philosopher 0 is thinking Philosopher 0 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 0 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 3 is thinking Philosopher 3 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 is thinking Philosopher 1 is thinking Philosopher 1 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 1 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 2 is thinking Philosopher 2 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 2 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 is eating. Philosopher 1 is eating. Philosopher 2 is eating. Philosopher 4 is eating. Philosopher 0 is eating. Philosopher 4 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 4 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 is thinking Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 4 is eating. Philosopher 0 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 0 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 0 is thinking Philosopher 0 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 0 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 0 is eating. Philosopher 2 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 2 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 2 is thinking Philosopher 2 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 2 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 2 is eating. Philosopher 4 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 4 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 is thinking Philosopher 4 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 4 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 4 is eating. Philosopher 3 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 3 is thinking Philosopher 3 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 3 is eating. Philosopher 1 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 1 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 1 is thinking Philosopher 1 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 1 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 1 is eating. Philosopher 1 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 1 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 1 is thinking Philosopher 1 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 1 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 1 is eating. Philosopher 0 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 0 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 0 is thinking Philosopher 0 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 0 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 0 is eating. Philosopher 3 dropped the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 dropped the left chopstick. Philosopher 3 is thinking Philosopher 3 picked up the right chopstick. Philosopher 3 picked up the left chopstick. Philosopher 3 is eating. ...(以後、永遠と哲学者が全員が思考と食事を繰り返す)

4.3の感想

- 意外と思考実験系の問題がOSの教科書に多いなという感じがした

4.4 教科書の問題 Chapter 12 ex 12.5

教科書の12.5の問題を解く、問題文は以下の通り

What is a basic tool? Give three examples of tools you use often.

和訳

basic toolとは何か? あなたがよく使うツールの例を3つ挙げよ。

答え(日本語)

basic toolとは、特に教科書の12章ではファイル/ディレクトリ操作、編集をするためのシェル、コマンドやエディタのことを指す

僕がよく使うツールは、zsh, nvim, tmuxである

各種の設定があるdotfiles

4.4の感想

- zsh, nvim, tmuxいいよね

4.5 教科書の問題 Chapter 9 ex 9.13

メールでは21.15と書かれていたがChapter 21に問題がなかった

9章(Real-Time Operating Systems and Microkernels)から問題を選ぶ

教科書の9.13の問題(実は#4.2でといた教科書の7.7と繋がっている)を解く、問題文は以下の通り、

Gauls whom we came across in the exercises on interprocess communication are back again here. GetAFix, the druid who makes the magic potion, uses herb concentrates for his magic potion. However in the preparation of the potion,4 some enzymes are used as catalysts. The concentration of enzymes affects the rate of reaction. Additionally, the volume of the herb concentrate and its temperature need to be regulated. Note that the total time for brewing is also critical. What kind of schedule would you propose to GetAFix? Will any one of the three scheduling methods, namely rate-monotonic, earliest deadline first or earliest laxity first, by itself be adequate?

和訳

プロセス間通信の演習で出会ったガリア人が、ここでも登場する。魔法薬を作るドルイドである、GetAFixはハーブの濃縮液を使っている。しかし、魔法薬の調合には触媒としていくつかの酵素が使われている。酵素の濃度は、反応速度に影響を与える。さらに、ハーブの濃縮液の量や温度も調節する必要がある。また、醸造にかかる総時間も重要である。GetAFixにどのようなスケジュールを提案したら良いだろうか。rate-monotonic、earliest deadline first、earliest laxity firstの3つのスケジューリングを行う方法のうち、どれか1つだけでも十分になるだろうか?

スケジューリングを行う方法をまとめる

rate-monotonic

- 特徴

- 周期の短いタスクは優先度が高くなる

- 固定優先度割り当て

- preemptive

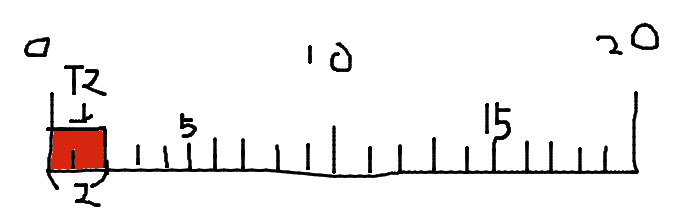

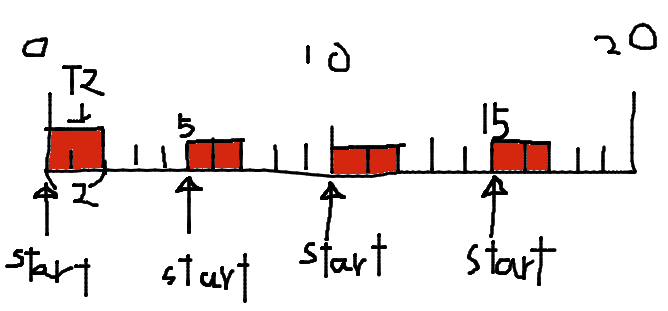

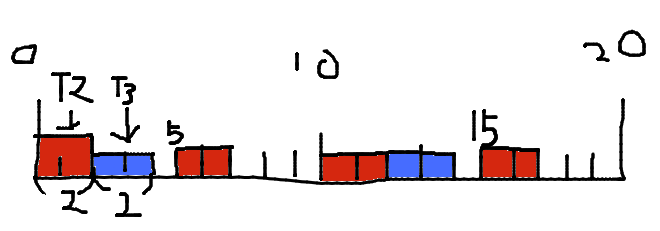

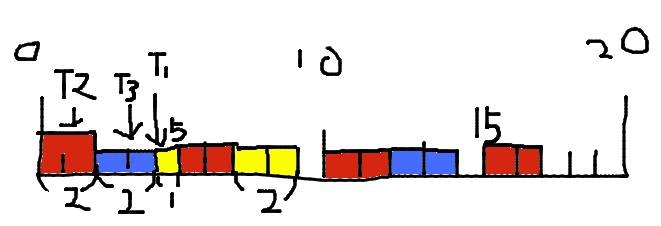

以下のタスクのスケジューリングを考える

| Task | Capacity(タスク実行時間) | Period(周期) |

|---|---|---|

| T1 | 3 | 20 |

| T2 | 2 | 5 |

| T3 | 2 | 10 |

Capacityはタスクの実行時間のことである

Periodはタスクの周期のことである

Periodが一番短い順にタスクの優先度が高くなる、一番短いT2に注目する

T2のCapacityは2なのでタスクの実行に2の時間がかかる

T2のPeriodは5なので5の倍数の時間にタスクが開始される

次に2番目にPeriodが短いT3に注目する

T3が10の倍数の時間にタスクが開始されるはずだが、T2のほうが優先される、T2が終わった後にT3のタスクが実行される

T1に注目する

T1が20の倍数の時間にタスクが開始されるはずだが、T2,T3のほうが優先される、T2,T3が終わった後にT1のタスクが実行される

T1の実行中にT2のPeriodの倍数の時間に到達したため、Periodが短いタスクであるT2が優先して実行され、長い方のT1が中断される、このようにタイマや割り込みなどで自動的にタスクが入れ替わるスケジューリングをPreemptiveという

図の目盛りの最大値が20である理由はそれぞれのタスクのPeriod、20, 5, 10の最小公倍数であるから

上記の例では、与えられた3つのタスクをスケジューリングすることに成功している

スケジュール可能である条件

nをタスクの数、Tを{T1, T2, ..., Tn}のタスクの集合と考えて、CiをTiのCapacity、PiをTiのPeriodと定義して

Σ[i=1→n]Ci/Pi

という式を作る

これがn(21/n-1)以下である、つまり

Σ[i=1→n]Ci/Pi <= n(2^(1/n)-1)

であるならば、タスクすべてを実行期限(デッドライン)内に完了することができる、つまりスケジュール可能である

earliest deadline first

- 特徴

- 最も実行期限が近いタスクを優先して実行する

- 動的に優先度が割り当てられる

- non-preemptive

スケジュール可能である条件

nをタスクの数、Tを{T1, T2, ..., Tn}のタスクの集合と考えて、CiをTiのCapacity、PiをTiのPeriodと定義して

Σ[i=1→n]Ci/Pi <= 1ならばスケジュール可能である

earliest laxity first

- 教科書にはearliest laxity firstが載っているページがこの問題ページにしか存在しない、調べてもLeast Laxity Firstしかでない

Least Laxity Firstが教科書の指すearliest laxity firstであるとして問題を解く

まず、laxity timeとはそのタスクを可能な限り速く実行するとしたときの実行期限までの余裕の時間である

- 特徴

- laxity timeが最小なタスクを優先して選択して実行する

- 動的に優先度を割り当てられる

- preemptive

スケジュール可能である条件

earliest deadline firstと同じで、nをタスクの数、Tを{T1, T2, ..., Tn}のタスクの集合と考えて、CiをTiのCapacity、PiをTiのPeriodと定義して

Σ[i=1→n]Ci/Pi <= 1ならばスケジュール可能である

答え(日本語)

提示されたrate-monotonic, earliest deadline first, earliest laxity firstの3つのスケジューリング手法の特徴を分類する

- 優先度の割り当て

- 静的

- rate-monotonic

- 動的

- earliest deadline first

- earliest laxity first

- 静的

- タスクの入れ替わり

- preemptive

- rate-monotonic

- earliest laxity first

- non-preemptive

- earliest deadline first

- preemptive

問題文の「酵素の濃度は、反応速度に影響を与える」という記述の解釈によって、答え方が変わる

酵素自体の濃度か、または、調合に使った1種類の酵素と全種類の酵素の割合のことを指しているのか

もし、酵素自体の濃度が反応速度に影響を与えるのであれば、タスクの切り替わりに関してpreemptive、non-preemptiveどちらでも構わない、その中でも静的に優先度が割り当てられているrate-monotonicはタスクの管理がしやすいので、rate-monotonicが最適と思われる

もし、調合に使った1種類の酵素と全種類の酵素の割合が影響を与えるのであれば、non-preemptiveなearliest deadline firstの一択となる

4.5の感想

- 結構難しかった

- スケジューリング手法について勉強できて楽しかった